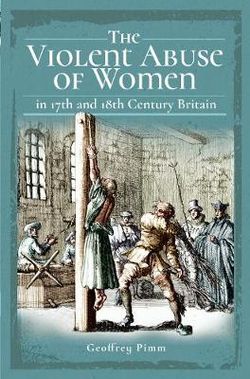

Synopsis:

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are the gateway between the medieval world and the modern, centuries when the western societies moved from an age governed principally by religion and superstition to an age directed principally by reason and understanding. Although the worlds of science and philosophy took giant strides away from the medieval view of the world, attitudes to women did not change from those that had pertained for centuries.

These new and unprecedented liberties thus gained by women were perceived as a threat by the leaders of society, and thus arose an unlikely masculine alliance against the new feminine assertions, across all sections of society from Puritan preachers to court judges, from husbands to court rakes.

This reaction often found expression in the violent and brutal treatment of women who were seen to have stepped out of line, whether legally, socially or domestically. Often beaten and abused at home by husbands exercising their legal right, they were whipped, branded, exiled and burnt alive by the courts, from which their sex had no recourse to protection, justice or restitution. Many of the most brutal forms of punishment were reserved exclusively for women, and even where the same, they were more savagely applied than would be the case for similar crimes committed by men.

What Pimm's book has done is catalogue the judicial use of violence as a form of punishment for crimes - or even perceived crimes - by women over the period of the 17th and 18th centuries, with a focus on Britain (and its satellite colonies).

This isn't a faint-hearted read as the violence depicted is often brutal, and may seem to today's reader, disproportionate to the crimes for which is was being administered as a form of judicial punishment. This is even more obvious when comparing the punishments metered out towards males for the same crimes (reference treason and coining).

Women were still considered to be subjected to the rule of the men in their lives - fathers, male relatives, husbands, employers. The were often the subject of violence at the hands of those who were said to have their own interests - and safety - at heart (see chapters on domestic violence, sexual abuse, abduction and clandestine marriage). Any form of countenance was viewed as rebellion against the social order and was therefore to be dealt with in as harsh as possible way in order to set an example to those women who may also consider "stepping out of line" and showing some form of independence of thought and spirit.

Pimm's book is divided into many categories - some of which overlap - which deal with not only the types of punishments used, but the types of crimes these were applied to. These chapters are often peppered with a snippets from social and legal papers and journals, in addition to contemporary writers (including Pepys, Swift and Johnson) - all of whom seem to think that their actions towards women were justified and beyond reproach.

Pepys writes in his diary for February 1621 " ... our little girl Susan is a most admirable slut and pleases us mightily ..." and, later in December 1664, after attending the home of friend wrote " ... I found occasion of sending him abroad, and then alone [with the man's wife] ... overcoming her resistance I did what I wanted to my contentment ..." after which he went home for his supper!

From a modern mind, I was startled by such callous and objectifying attitudes, even more so when realising that this was considered "normal". Even more disturbing was that many punishments were carried out in public with some observers gaining sexual gratification from such public displays of a woman's nakedness being exposed, especially to the whip, which lead to punishments being metered out in private - "..... it is a shameful indecency for a woman to expose her naked body to the sight of men and boys, as if it were designed rather to feat the eyes of the beholders that to correct vice ..." - really as if this were her choice!

Like today, the onus of proof of crime was often charged upon the female victim, who whether vindicated or not, was still the victim of judicial violence - usually the lash or the wipe as women were still blamed or were held accountable for being the cause of violence against them - "the sins of Eve" - that women were responsible for leading men astray; and as men were their betters, the punishment should be all the more harsh.

This is a fascinating read for the student of both social and legal history, though I won't whitewash the fact that our modern day sensibilities (such as they are) will not only be offended but challenged. Having said that, one wonders if we have advanced as far as we think - or would like to think - that we have with regards to attitudes towards women. Not the least bit thought provoking.

suggested further reading:

No comments:

Post a Comment