Synopsis: On 16th August 1860 wealthy widow Mary Emsley was murdered in her own home. The investigation that followed had an abundance of suspects, from disgruntled step children concerned about their inheritance and an admirer repeatedly rejected by the widow, to a trusted employee, former police officer and spy. The eventual public trial was dominated by surprise revelations and shock witnesses, before culminating with one of the final public executions at Newgate. But was an innocent person sent to the gallows?

Synopsis: On 16th August 1860 wealthy widow Mary Emsley was murdered in her own home. The investigation that followed had an abundance of suspects, from disgruntled step children concerned about their inheritance and an admirer repeatedly rejected by the widow, to a trusted employee, former police officer and spy. The eventual public trial was dominated by surprise revelations and shock witnesses, before culminating with one of the final public executions at Newgate. But was an innocent person sent to the gallows?

Years after the case was closed Sherlock Holmes author Arthur Conan Doyle became convinced a miscarriage of justice had occurred but was unable to find the real killer. After confounding the best detectives for years, the case has finally been solved by bestselling author Sinclair McKay.

From Cressida Connolly in The Spectator:

As in all the best Agatha Christies, the person who is murdered here is so universally disliked that suspicion may fall on almost anybody who knew her. Despite owning huge swathes of property, the widowed Mary Emsley employs no servants, living alone in a house she keeps locked and shuttered at night. Suspicious, stingy and scathing, she is all but friendless. She has no children and often remarks that she would sooner leave her considerable wealth to create almshouses than to her various kin. She is in the habit of ejecting any tenant who falls into even a week’s arrears. She is insensible to pleading. Some of her money is kept hidden in her coal store, but most is reinvested into housing stock. In short, she is a miserable miser.

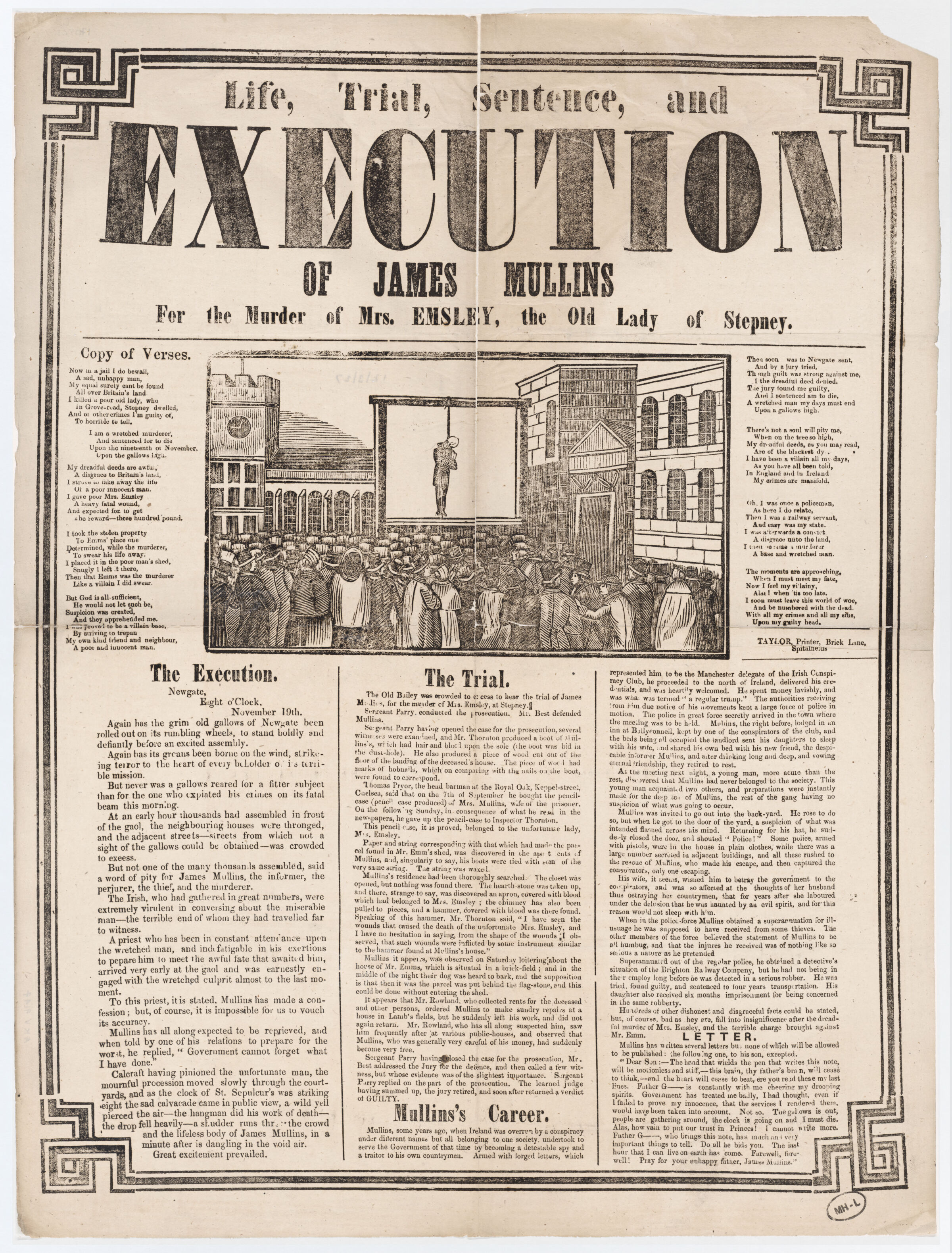

So it is hard to feel too sorry when we learn that Mrs Emsley has been bludgeoned to death on the third floor of her own home one warm August night in 1860. There is a bloody footprint on the landing, but no sign of forced entry. She must have admitted the killer herself. The question here is less why she was killed, than by whom. For although a man named James Mullins was tried and hanged for the murder, many did not believe him to have been the true culprit. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, examining the details of the case some years later, was flummoxed by it. Sinclair McKay posits a new idea of his own. His villain is someone we have met earlier on in the story; someone who knew Mrs Emsley and was a frequent visitor; someone who hoped, in getting rid of her, to gain an inheritance.

It’s a plausible and enjoyably creepy theory, although in the absence of fingerprinting and forensics, we will never really know. A boot with human hairs attached to it was found in the lodging house of the accused’s wife, and Mullins had certainly pilfered from the widow. But these were slender findings with which to take a man’s life, and McKay does a fine job of dismantling them as proof of guilt.

From Craig Brown in The Daily Mail:

Did he actually commit the crime that sent him to the scaffold? Writing about the case 40 years later, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, felt that his guilt should be reclassified as ‘unproven’, but McKay is completely convinced that Mullins was innocent.

With elaborate taran-taras, he has waited until the last two chapters in his book to reveal the true identity of the guilty party. My lips are sealed. All I will say is that his choice of the real villain is ingenious, and artistically satisfying, too, in that it would have pleased Wilkie Collins, or even Conan Doyle.

But is it true? Perhaps it is, and perhaps it isn’t. But it doesn’t strike me that, based on McKay’s fairly slim evidence, a sensible jury would convict. My own suspicion is that Mrs Emsley might have let a total outsider into her house – she had advertised a sale of wallpaper, so would have been expecting strangers – which means that her murderer might have been anyone.

But is it true? Perhaps it is, and perhaps it isn’t. But it doesn’t strike me that, based on McKay’s fairly slim evidence, a sensible jury would convict. My own suspicion is that Mrs Emsley might have let a total outsider into her house – she had advertised a sale of wallpaper, so would have been expecting strangers – which means that her murderer might have been anyone.

And I suspect, too, that McKay is not quite as convinced by his solution as his publishers, who confidently state that he has finally revealed the ‘true murderer’, would have us believe.

read also:

No comments:

Post a Comment