Synopsis: Magna Carta clause 39: No man shall be taken, imprisoned, outlawed, banished or in any way destroyed, nor will we proceed against or prosecute him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.

This clause in Magna Carta was in response to the appalling imprisonment and starvation of Matilda de Braose, the wife of one of King John's barons. Matilda was not the only woman who influenced, or was influenced by, the 1215 Charter of Liberties, now known as Magna Carta. Women from many of the great families of England were affected by the far-reaching legacy of Magna Carta, from their experiences in the civil war and as hostages, to calling on its use to protect their property and rights as widows. Ladies of Magna Carta looks into the relationships - through marriage and blood - of the various noble families and how they were affected by the Barons' Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken.

Including the royal families of England and Scotland, the Marshals, the Warennes, the Braoses and more, Ladies of Magna Carta focuses on the roles played by the women of the great families whose influences and experiences have reached far beyond the thirteenth century.

Including the royal families of England and Scotland, the Marshals, the Warennes, the Braoses and more, Ladies of Magna Carta focuses on the roles played by the women of the great families whose influences and experiences have reached far beyond the thirteenth century.

Background:

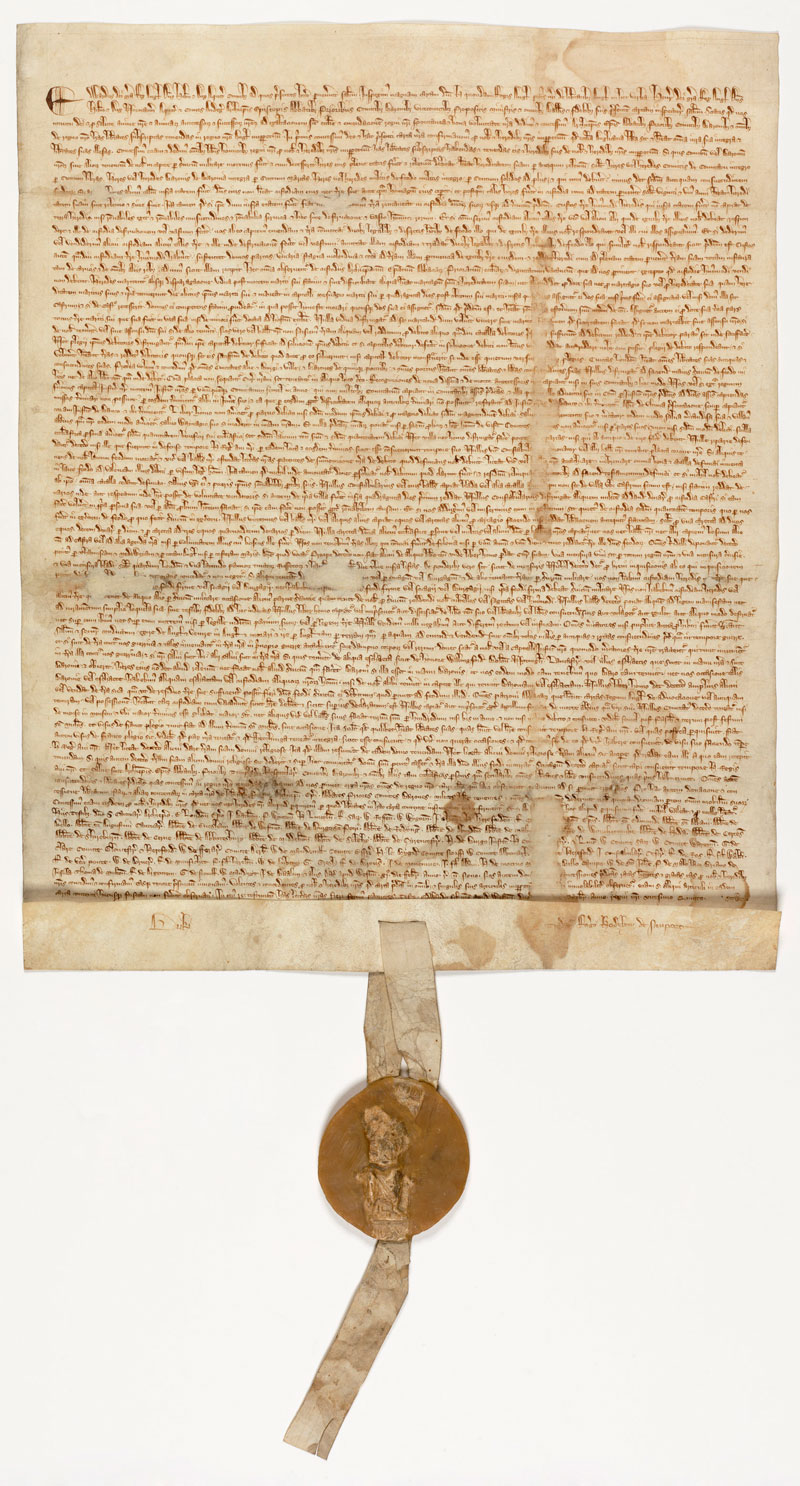

Magna Carta was first drafted by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury to make peace between the unpopular King John of England and a group of rebel barons. It promised the protection of church rights, protection for the barons from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, and limitations on feudal payments to the Crown, and was to be implemented through a council of 25 barons. Neither side stood behind their commitments, and the Charter was annulled by Pope Innocent III (claiming John had signed under duress), which ultimately lead to the First Barons' War.

So what did Magna Carta do for women?

Most of the Magna Carta had little directly to do with women. The chief effect of the Magna Carta on women was to protect wealthy widows and heiresses from arbitrary control of their fortunes by the crown, to protect their dower rights for financial sustenance, and to protect their right to consent to the marriage.

Magna Carta names 34 men but mentions only three women: John's queen (Clause 61), and the sisters of King Alexander II of Scotland and not one was specifically named. This reflects "the inequalities between men and women, and in particular the way women played a very limited part in public affairs." David Carpenter Prof of Medieval History, Kings College London. Carpenter goes on to say that "far from giving equal treatment to all", the Magna Carta was a "divided and divisive document, often reflecting the interests of a baronial elite" who were essentially "a few hundred strong in a population of several millions".

Magna Carta names 34 men but mentions only three women: John's queen (Clause 61), and the sisters of King Alexander II of Scotland and not one was specifically named. This reflects "the inequalities between men and women, and in particular the way women played a very limited part in public affairs." David Carpenter Prof of Medieval History, Kings College London. Carpenter goes on to say that "far from giving equal treatment to all", the Magna Carta was a "divided and divisive document, often reflecting the interests of a baronial elite" who were essentially "a few hundred strong in a population of several millions".

We begin with a look at the political history of the reigns of Richard I, John (under who things really came to a head), and Henry III; and the increased discontentment among the nobles with both John and his policies which culminated in the document known as the Great Charter or Magna Carta.

Now I will look at now in further detail, looking at the specific clauses from the 1215 Magna Carta and is later editions, that are applicable to women:

Clause (6) Heirs shall be married without disparagement, so that before the marriage be contracted, it shall be notified to the relations of the heir by consanguinity (by 1297 this - Clause 5 - was edited down to one sentence: Heirs shall be married without disparagement).

While not directly about women (the heir/s being referred to in the above is in the masculine), it could protect a woman’s marriage in a system where she did not have full independence to marry whomever she wanted.

Clause (7) At her husband’s death, a widow may have her marriage portion and inheritance at once and without trouble. She shall pay nothing for her dower, marriage portion, or any inheritance that she and her husband held jointly on the day of his death. She may remain in her husband’s house for forty days after his death, and within this period her dower shall be assigned to her.

Clause (7) A widow, after the death of her husband, shall immediately, and without difficulty, have her freedom of marriage and her inheritance; nor shall she give anything for her dower, or for her freedom of marriage, or for her inheritance, which her husband and she held at the day of his death; and she may remain in the principal messuage of her husband, for forty days after her husband’s death, within which time her dower shall be assigned; (†) unless it shall have been assigned before, or excepting his house shall be a castle; and if she departs from the castle, there shall be provided for her a complete house in which she may decently dwell, until her dower shall be assigned to her as aforesaid. (1216 Charter of Henry III)

Clause (7) A widow, after the death of her husband, shall immediately, and without difficulty, have her freedom of marriage and her inheritance; nor shall she give any thing for her dower, or for her freedom of marriage, or for her inheritance, which her husband and she held at the day of his death; and she may remain in the principal messuage of her husband, for forty days after her husband's death, within which time her dower shall be assigned; unless it shall have been assigned before, or excepting his house shall be a castle; and if she depart from the castle, there shall be provided for her a complete house in which she may decently dwell, until her dower shall be assigned to her as aforesaid. And she shall have her reasonable estover [allowance] within a common term. And for her dower, shall be assigned to her the third part of all the lands of her husband, which were his during his life, except she were endowed with less at the church door. (1217 Charter of Henry III & as Clause 6 in the 1225 Charter of Henry III, Clause 6 in the 1297 Charter of Edward I)

This clause protected the right of a widow to have some financial protection after marriage and to prevent others from seizing either her dower or other inheritance she might be provided with. It also prevented her husband’s heirs from making the widow vacate her home immediately on the death of her husband.

Clause (8) No widow shall be compelled to marry, so long as she wishes to remain without a husband. But she must give security that she will not marry without royal consent, if she holds her lands of the Crown, or without the consent of whatever other lord she may hold them of.

Clause (8) No widow shall be compelled to marry, whilst she is willing to live without a husband; but yet she shall give security that she will not marry without our consent, if she hold (lands) of us, or without the consent of her lord if she hold of another. (1216 Charter of Henry III)

Clause (7) No widow shall be compelled to marry, whilst she is willing to live without a husband; but yet she shall give security that she will not marry, without our consent, if she hold of us, or without the consent of her lord if she hold of another. (1225 Charter of Henry III & 1297 Charter of Edward I)

This Clause permitted a widow to refuse to marry and prevented (at least in principle) others from coercing her to marry. It also made her responsible for getting the king’s permission to remarry, if she was under his protection or guardianship, or to get her lord’s permission to remarry, if she was accountable to a lower level of nobility. While she could refuse to remarry, she was not supposed to marry just anyone. Given that women were assumed to have less judgment than men were, this was supposed to protect her from unwarranted persuasion. Over the centuries, a good number of wealthy widows married without the necessary permissions. Depending on the evolution of the law about permission to remarry at the time, and depending on her relationship with the crown or her lord, she might incur heavy penalties or forgiveness.

However, to put this Clause into context, most women were either under the 'protection' of their father or husband. Widows were deemed to be under the 'protection' of the King but as Susanna Annesley (Kings College, London) points out "for all the undeniable benefits of Magna Carta there were still considerable loopholes that the king could exploit and widows often still found themselves at the mercy of a male overlord, whether he be a member of their own family or the king himself."

Clause (11*) And if any one shall die indebted to the Jews, his wife shall have her dower and shall pay nothing of that debt; and if children of the deceased shall remain who are under age, necessaries shall be provided for them, according to the tenement [land holding] which belonged to the deceased: and out of the residue the debt shall be paid, saving the rights of the lords. [service due to his feudal lords] In like manner let it be with debts owing to others than Jews.

This clause (omitted from later editions, but included the Charter confirmed by Henry III in 1216) also protected the financial situation of a widow from moneylenders, with her dower protected from being demanded for use to pay her husband’s debts. Under usury laws, Christians could not charge interest, so most moneylenders were Jews.

Clause (26) If any one holding of us a lay fee dies, and the sheriff or our bailiff, shall show our letters-patent of summons concerning the debt which the deceased owed to us, it shall he lawful for the sheriff or our bailiff to attach and register the chattels of the deceased found on that lay fee, to the amount of that debt, by the view of lawful men, so that nothing shall he removed from thence until our debt he paid to us; and the rest shall he left to the executors to fulfil the will of the deceased; and if nothing be owing to us by him, all the chattels shall fall to the deceased, saving to his wife and children their reasonable shares.

This is now Clause 18 under the 1216 Charter of Henry III and Clause 19 in the 1217 Charter of Henry III and Clause 18 in the 1225 Charter of Henry III and 1297 Charter of Edward I. It speaks specifically of any debt owed to the Crown, which will be taken from the deceased's estate 9ie: removal and sale of goods and chattels). It no debt is owing, then the will can be executed in favour of the widow and heirs.

The following is one of the most important Clauses and is still in effect today.

Clause (39) No free-man shall he seized, or imprisoned, or dispossessed, or outlawed, or in any way destroyed; nor will we condemn him, nor will we commit him to prison, excepting by the legal judgment of his peers, or by the laws of the land.

It was variously edited as follows in following Charters as:

Clause (30) No free-man shall be taken or imprisoned, or dispossessed or be outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed; nor will we condemn him, nor will we commit him to prison, excepting by the legal judgment of his peers, or by the laws of the land. (1216 Charter of Henry III and as Clause 32 in the 1217 Charter of Henry III)

Clause (29) No free-man shall be taken, or imprisoned, or dispossessed, of his free tenement, or liberties, or free customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed; nor will we condemn him, nor will we commit him to prison, excepting by the legal judgment of his peers, or by the laws of the land. To none will we sell, to none will we deny, to none will we delay right or justice (this last sentence was a separate Clause in previous editions but in incorporated with this clause in the 1225 Charter of Henry III and 1297 Charter of Edward I).

This significant Clause states that no "freeman" is to be imprisoned or punished without the lawful judgement of his peers or the law of the land. And one must remember, that this Charter was only applicable to all "free men" not "all men". And whilst "freemen" could have been taken to include "free women", women could not sit on juries, so they would always be judged by men. And really, only those with access to the King's courts, could have access to the King's justice.

Clause (54) No man shall he apprehended or imprisoned on the appeal of a woman, for the death of any other man except her husband.

This Clause (numbered 37 in the 1216 Charter of Henry III / Clause 38 in the 1217 Charter of Henry III / Clause 34 in 1297 Charter of Edward I) wasn’t so much for protection of women but prevented a woman’s appeal from being used to imprison or arrest anyone for death or murder. The exception was if her husband was the victim. This fits within the larger scheme of understanding of a woman as both unreliable and having no legal existence other than through her husband or guardian. so it actually reduced and limited women's right to be heard as a witness in court.

Clause (59*) We shall do to Alexander King of Scotland, concerning the restoration of his sisters and hostages, and his liberties and rights, according to the form in which we act to our other barons of England, unless it ought to he otherwise by the charters which we have from his father William, the late King of Scotland; and this shall be by the verdict of his peers in our court.

This clause (omitted from later editions) deals with the specific situation of the sisters of Alexander, king of Scotland who were held as hostages by John to assure a peace. This assured the return of the princesses. Six years later, John’s daughter, Joan of England, married Alexander in a political marriage arranged by her brother, Henry III.

Bennett Connolly wanted: (1) to show how women influenced and were influenced by Magna Carta; how they were a central part of the struggle to bring about such a document, and to ensure that its clauses were being kept; and (2) to "examine how ... Magna Carta influenced and impacted the women of the 13th century" and chose to present the ladies documented within the context of their families.

So, was the brief met - partly yes and partly no. So let us take the second part - influence and impact, and the presentation of the ladies. Yes, the ladies were definitely shown in the "context of their families" - and great detail and attention is given to setting out the family structure and connections. They made for very good examples of how certain clauses of the Magna Carta could be applied and how some women were able to steer their own course during this period. Women , as we have seen, were chattels - under the governance of their fathers and other male relations, their husbands, and to a degree their lords or monarchs. They had no say on whom they married and when, what happened to any children from said union (if any), and what happened tho their husband's estates on his death. However, having said that, there were a couple of ladies listed whom the author claims "had no political role" or "... had little to do with Magna Caata .." - one wonders why they were included at all.

Let us not forget that the women affected, impacted or influenced by the Magna Carta were largely the elite among women: noblewomen, heiresses and wealthy widows. Under common law, once a woman was married, her legal identity was subsumed under that of her husband: the principle of coverture. As mentioned, women had limited property rights, but widows had a bit more ability to control their property than other women did. The common law also provided for dower rights for widows: the right to access a portion of her late husband's estate, for her financial maintenance, until her death.

Let us not forget that the women affected, impacted or influenced by the Magna Carta were largely the elite among women: noblewomen, heiresses and wealthy widows. Under common law, once a woman was married, her legal identity was subsumed under that of her husband: the principle of coverture. As mentioned, women had limited property rights, but widows had a bit more ability to control their property than other women did. The common law also provided for dower rights for widows: the right to access a portion of her late husband's estate, for her financial maintenance, until her death.

As to their influence on Magna Carta, this falls into the realm of conjecture and speculation, and the examples given are very narrow and not really enough to provide a satisfactory proof. In this, we are specifically looking at the example of Matilda (Maud) de Braose, who by a careless throw-away line, did arouse such suspicion and jealousy in the King that it condemned her family. Bennett Connolly claims that "[clause 30] .. was brought into existance through the tragedy and suffering of Matilda de Braose and her family .." and ".. given the extent of the family's suffering at the hands of King John, it seems only fair that the dramatic experiences of the de Braose women are enshrined in no less than three clauses of Magna Carta - 7, 8, 9 ...". But can we know this for certain? Was this the only example of John's cruel treatment of noble prisoners? No, because we are aware of the fate of his nephew Arthur and also of twenty-two nobles, captured at Mirebeau, who suffered the same fate as Matilda de Braose. Matilda's case in point was but one strand among many.

In fact it was William Marshall who is claimed to have said: ".. be on alert against the King: what he thinks to do to me, he will do to each and every one of you, or even more, if he gets the upper hand over you ..". As a loyal supporter of King John and of the Magna Carta, his words carry much weight, and in this, the fate of the de Braose's can been viewed.

Did Bennett Connolly adequately demonstrate that her chosen subjects ".. were central to the struggle.." and did indeed ".. ensure that its clauses were being kept.." - no, I personally do not think that this was addressed. Not even Ela of Salisbury or Nicholaa de Haye, in their capacities as Sheriff, exert any influence on the enforcement of Magna Carta. We can only say with some degree of certainty that it was Eleanor, wife of Simon de Montfort Earl of Leicester, who notably aided the fight for political reform led by her husband in the Barons' Wars, and suffered for her opposition to both her brother King Henry III and nephew Edward I. But this was much later and had little to do with the creation of Manga Carta of King John.

For me personally, I would have set this out a little differently with chapters dedicated to each of the pertinent clauses and examples then given in support, not just biographies of a select few women and then trying to tie them into the relevant clauses..

As for Magna Carta, it was a failure in the short term, but it was a step in creating and defining a set of standards for royalty and nobility. The King was no longer above the law but held accountable through his nobles. After many amendments, only three clauses are left enshrined in law today.

No comments:

Post a Comment