This three-volume Chronicle gives us a gripping and wide-ranging picture of a period characterized by harsh brutality, conflict and betrayal but at the same time by the ideals of chivalry, memorably personified in figures such as the Black Prince and Bertrand du Guesclin. At its centre is the chilling portrait of King Pedro, a brilliantly constructed image of self-destructive evil.

Wednesday, October 28, 2020

Chronicle of King Pedro Volumes 1 - 3 ed by Peter Such

This three-volume Chronicle gives us a gripping and wide-ranging picture of a period characterized by harsh brutality, conflict and betrayal but at the same time by the ideals of chivalry, memorably personified in figures such as the Black Prince and Bertrand du Guesclin. At its centre is the chilling portrait of King Pedro, a brilliantly constructed image of self-destructive evil.

Childhood, Youth and Religious Minorities in Early Modern Europe by Tali Berner

Saturday, October 24, 2020

Review: The Secret Diaries of Juan Luis Vives by Tim Darcy Ellis

Jewish Women and Their Salons by Emily Bilski & Emily Braun

Baldric of Bourgueil: "History of the Jerusalemites" translated by Susan Edgington

The Woman Who Discovered Printing by T.H. Barrett

Thursday, October 22, 2020

Blog Tour: Sons of Rome

Sons of Rome is the first book in the brand new Rise of Emperors series, an action-packed historical thriller set in the 3rd century AD. It follows the lives of two men whose destinies are inextricably linked after a chance meeting in the city of Treverorum in their youth. They must share glory and heartbreak along with the Roman empire itself as it endures an era of tyranny and dread.

But just how did two authors decide to bring two characters together - in the same book. Well, here's how it all came about from the authors themselves.

Wednesday, October 21, 2020

Review: The Lost & Damned by Olivier Norek

Tuesday, October 20, 2020

Review: Charles I's Executioners by James Hobson

This is a more simplified version - it is not strictly a biography of the nearly 135 participants in the trial and execution of King Charles I of England, nor does it go into any great detail about the English Civil War (it is assumed that the reader has some fore-knowledge). What Hobson has done instead is present a series of themed vignettes of the 59 who actually signed the warrant of execution for King Charles I of England.

Review: Murder During The Hundred Years War by Melissa Julian-Jones

Using contemporary documents and accounts and past scholarship, Melissa Julian-Jones presents the reader with various hypotheses, whilst examining in detail both the members of the household (including the wife) and the extended family connections "... to consider likely scenarios ..". As such, it is necessary to gather as much background information as possible to contextualise possible narratives. In this day and age, family and familial connections were very important and it is necessary to delve into the background of all associated with this case in order to eliminate possible suspects and motives.

Saturday, October 17, 2020

Review: The Highland Battles by Chris Peers

Blog Tour - Sons of Rome

I am participating in the upcoming Blog Tour for "Sons of Rome" by Gordon Doherty & Simon Turney. "Sons of Rome" is the first part of the story of Constantine the Great and Maxentius. Feel free to drop by my blog on the 22nd October to learn how this amazing story came about.

Saturday, October 10, 2020

Howdunit by Martin Edwards

Priestess of Pompeii: The Initiate’s Journey Book I by Sandra Hurt

‘War’ by Margaret MacMillan

Women, Writing and Religion in England and Beyond, 650–1100

At some point between 776 and 786, an English nun in the Bavarian monastery of Heidenheim wrote four lines in a secret code in the space between the end of one Latin text and the beginning of another. She was the author of both—accounts of the lives of Saints Wynnebald and Willibald—but had left them anonymous, describing herself at the start of one as no more than an “indigna Saxonica” (“unworthy Saxon woman”). The code was deciphered only in 1931, by the scholar Bernard Bischoff. Decoded and translated from the Latin, the line reads, “I, a saxon nun named Hugeburc, composed this.” In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf observed that “Anon…was often a woman.” Sometimes Anon was hiding in plain sight.

At some point between 776 and 786, an English nun in the Bavarian monastery of Heidenheim wrote four lines in a secret code in the space between the end of one Latin text and the beginning of another. She was the author of both—accounts of the lives of Saints Wynnebald and Willibald—but had left them anonymous, describing herself at the start of one as no more than an “indigna Saxonica” (“unworthy Saxon woman”). The code was deciphered only in 1931, by the scholar Bernard Bischoff. Decoded and translated from the Latin, the line reads, “I, a saxon nun named Hugeburc, composed this.” In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf observed that “Anon…was often a woman.” Sometimes Anon was hiding in plain sight.Thursday, October 8, 2020

Happy Birthday Women of History Blog

Wednesday, October 7, 2020

Jane Harper's secret ambition was to write a book. Now she's sold millions

When Jane Harper was invited to visit the set during filming of her first novel, The Dry, she took full advantage. The director, Robert Connolly, was on location in outback north-west Victoria and needed extras for a scene being shot in a small church. Harper didn't need to be asked twice, showing up with about a dozen friends and family ready to play grieving townspeople.

When Jane Harper was invited to visit the set during filming of her first novel, The Dry, she took full advantage. The director, Robert Connolly, was on location in outback north-west Victoria and needed extras for a scene being shot in a small church. Harper didn't need to be asked twice, showing up with about a dozen friends and family ready to play grieving townspeople.Tuesday, October 6, 2020

Edward the Confessor by Tom Licence

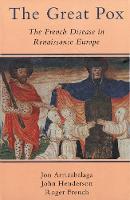

The Great Pox by Jon Arrizabalaga, John Henderson, Roger French

One hundred and fifty years after the Black Death killed a third of the population of Western Europe, a new plague swept across the continent. The Great Pox—commonly known as the French disease—brought a different kind of horror: instead of killing its victims rapidly, it endured in their bodies for years, causing acute pain, disfigurement, and ultimately an agonizing death.

One hundred and fifty years after the Black Death killed a third of the population of Western Europe, a new plague swept across the continent. The Great Pox—commonly known as the French disease—brought a different kind of horror: instead of killing its victims rapidly, it endured in their bodies for years, causing acute pain, disfigurement, and ultimately an agonizing death.Turns Out, Elizabethan Playwright and Poet Laureate Ben Jonson was a Murderer

From CrimeReads:

From CrimeReads:Monday, October 5, 2020

Making of the Neville Family in England, 1166-1400 by Charles Young

- The Nevills of Middleham: England's Most Powerful Family in the Wars of the Roses by KL Clark

- Warwick the Kingmaker by Michael Hicks

Beth Doesn't Always Die in Little Women. Sort Of

Sunday, October 4, 2020

Review: The Murder of Edward VI by David Snow