Synopsis: Paris 1396: Scribe Christine de Pizan is shocked when the Duke of Orleans' fools find a baby, wrapped in rags and covered in sores, abandoned in the palace gardens. Was there really a wicked plan to substitute the child for the queen's own baby daughter and blame the Duchess of Orleans, Valentina Visconti? Who would commit such an evil act, and why?

Synopsis: Paris 1396: Scribe Christine de Pizan is shocked when the Duke of Orleans' fools find a baby, wrapped in rags and covered in sores, abandoned in the palace gardens. Was there really a wicked plan to substitute the child for the queen's own baby daughter and blame the Duchess of Orleans, Valentina Visconti? Who would commit such an evil act, and why? Accused of being a sorceress, Valentina is the victim of much slander and has powerful enemies at the palace, where rumours of witchcraft and superstition run riot. Convinced of the duchess's innocence, Christine is determined to uncover the truth, and soon makes a number of disturbing discoveries. Could the palace fools be the key to unlocking the mystery?

This is the third in the series featuring Christine de Pisan, and I would suggest starting from the beginning with In the Presence of Evil and In the Shadow of the Enemy and many of the characters and themes in this instalment have their origins in the first two books, as does the historical background.

|

| Valentina Visconti |

Some Historical Background:

Valentina was born in Milan as the second of the four children of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, first Duke of Milan, and his first wife Isabelle, a daughter of King John II the Good of France. She was therefore she was the cousin of the current King of France, Charles VI and niece of Philip, Duke of Burgundy. Isabeau of Bavaria was the granddaughter of Bernabò Visconti, whom Gian Galeazzo treacherously displaced in Milan, and thus a bitter rival of both Valentina and her father.

|

| Louis I of Orleans |

As a result of the ongoing power struggles for control of the King coupled with the intrigues of the courtiers and nobles - each with their own agendas - and the enmity of the queen, salacious gossip abounded. Pre-eminant among those rumours were that Valentina, who was very close to the King, had bewitched him (causing his madness); and that Isabeau was having an affair with Louis, Valentina's husband and brother of the King.

From the late 1390s, Orléans - ever in need of greater funds in view of the smallness of his appanage - was exercising much more pressure on the financial officialdom in order to sustain his policies and incurring the unpopularity for which he was to pay dearly. It was here that the clash with Burgundy really became truly venomous. The costs of political stability in the period were enormous. Payments, pensions and one-off presents to courtiers, great officers of the crown and great nobles were a substantial drain on yearly revenues. Hence the competition for control of the revenues. This rivalry between Louis of Orleans and Philip of Burgundy was such that the end result was outright civil war.

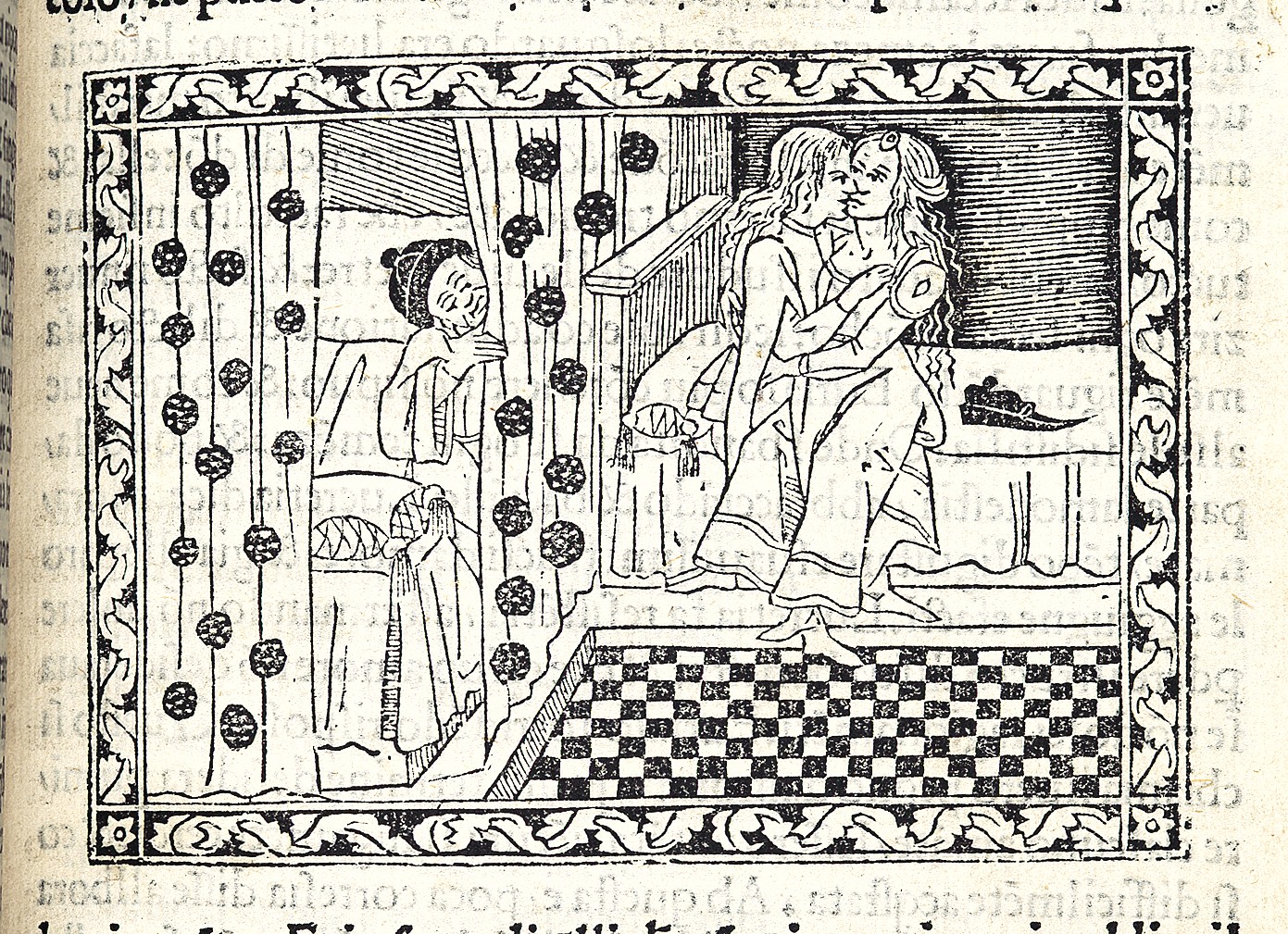

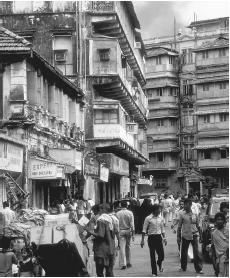

Into this meltingpot of rumour and innuendo, throw in some talk of witchcraft and sorcery. The medieval court was the centre of political life during the Middle Ages, where officials of all ranks attended to governmental affairs. As a place of wealth, influence and power, intrigues were an ordinary suspicion and the court was the ideal environment for popular magical practices to cultivate as the employment of magical practitioners provided great political advantages.

Astrologers delivered a calendar of ideal times for rulers to make political decisions and alchemists, the possibility of riches and prolonged life. A knowledge of chemicals and herbs would have proved useful in intrigues where poisons and love spells were in demand. As fear and usage of magic was ever present, courtiers engaged in the practice of possessing precious stones whose properties protected them from such inflictions. Within the court there were also those who, whilst brandishing significant amounts of influence, held no formal office. As such, those driven by these ambitions employed magic to assist in their plots to beat rivals and gain their desired position. However, in this turbulent political climate fear and suspicion of magical practitioners and accusations of harmful magic increased. Even the Duke of Orelans was not immune when he too was accused of using sorcery (specifically a waxen image said baptized by a monk) against Charles VI (1392).

Finally both ‘factions’ sought to appeal to public opinion by distributing political programs in the form of letters, pamphlets, songs and pasquils (lampoons) for street distribution which stressed the good of the kingdom, the control of abuses and “reform”, and were a much used weapon in turning public opinion against a potential rival through scandal and innuendo.

With public and court opinion against her, rumours of sorcery and witchcraft, Valentina was ultimately exiled from the court and forced to leave Paris. She remained at Blois till her death in 1408.

Gian Galeazzo reacted to gossip about Valentina at the French Court by threatening to declare war on France and to send knights to defend his daughter's honor. There is no record of him doing so. However, after the disaster of Nicopolis (1396), he was strongly suspected of having betrayed the Crusaders as vengeance for his daughter being accused of being behind the illness of King Charles VI of France, as well as for France's increasing control over the city of Genoa that he had attempted to hamper, and for which he had been rebuked by Enguerrand VII de Coucy before the battle.

Now to those other characters - the Fools. Court dwarfs - not to be confused with jesters who were employed for entertainment and amusement - were owned and traded amongst the people of the court, and delivered as gifts to fellow kings and queens. Dwarfs usually had a permanent function and were registered in the personnel rolls as "court dwarf", "personal dwarf" or "chamber dwarf". This enabled them to play an important role in ceremonial culture and gave them close access to the ruler. This close relationship led to multiple roles beyond the foolish task as a natural clown. Court dwarfs served as a substitute for children, companion for royal children, or even diplomats. At the end of their career, these privileged dwarfs would usually receive a pension and other benefits.

Bayard touches upon many of the above background topics - the fools, magic, alchemy, sorcery - to provide us with an insider's view of the French Court. We are reunited with Christine's old foe, Henri le Picout, and allies Marion, the prostitute and Brother Michel of the Abbey of Saint Denis. Whilst not particularly action driven, the reader will find themselves so swept up in the storytelling that they will not realise just how far they have been drawn along. I am looking forward to the next in the series.